Visiting Canberra this week, I've been struck by the arrangement of

the national Mall. Inspired by Washington DC perhaps, a broad green

sward descends from the parliament house to the lake: and across the

lake, it continues in an avenue of memorials leading to the Australian

national war memorial.

The effect is impressive: from the door of the Parliament, your eye

cannot help being drawn to the war memorial. It's as if the war dead

are watching over all who come and go from the seat of Australian

Democracy, reminding them of the blood-price of that place. I guess

the American Mall includes a number of war memorials, and the British

Offices of State overlook the Cenotaph, but the effect in Canberra

seems particularly striking: attention is not on a statesman, or a

nation-builder, or a king, but upon those whose lives were laid down.

Each name on that memorial represents a life broken, a family

shattered. Each individual loss seems callous and senseless. Each

individual could have been someone else, were it not for that stray

bullet, that piece of shrapnel, the path of that disease, that

particular fire: though some undoubtedly were in harm's way precisely

because of a sense of duty or as a result of conspicuous valour.

But the combined effect of those individuals is something else

entirely. Wars arise for good reasons and bad: undoubtedly, some

should not have been fought. Some have genuinely, measurably, reduced

the amount of tyrrany in the world. Notwithstanding a few WW2

expeditions by the Japanese, Australia's borders have never really

been threatened since European settlement: but her sons (and

daughters) have travelled to Europe, Asia, Africa, for causes

percieved as just.

Can we decry that? The criteria for a Just War seem defensible: there

are situations when an aggressor can be stopped only by the use of

deadly force. Our willingness and ability to act may be patchy, but

that does not diminish the value or worthiness of doing so.

Where is today's Christian in this? In the days of conscription, our

parents and grandparents struggled with this issue in a way that few

of us have to: pacifisim and conscientious objection was no coward's

way, but it certainly wasn't the route of social acceptability. Most

of the time, few of us think about it at all, I imagine.

When bringing military remembrance into church, we often give thanks

for the freedoms we enjoy - not least the freedom to worship - these

having been brought about by those who fought and died `for freedom'.

Whether freedom to worship is the thing we should be most thankful

for, I'm not sure. But more importantly, I'm not certain that that

line of thinking holds water in every case - the Just War criteria are

not crafted around the concept of freedom, as such. Its undoubtedly

true that in some conflicts our own freedom has been enhanced by

fighting to install decidedly non-freedom-loving regimes in foreign

parts.

It seems to me that the main point of occasional wartime remembrance

in worship is for the sake of the pastoral care of those touched by

war and conflict: delving deeply into geopolitics is better left to a

differnt context. Too readily we wander into a kind of Christian

nationalism which rather confuses the kingdoms (and republics) of this

world with the kingdom of God: there's much sloppy thinking here, and

its best avoided altogether.

I can only respect those named on the Australian war memorial: and on

memorials in towns and villages across the whole of Europe - and I

imagine America and much of the rest of the world. Would that we

could say "never again": but while the world contains leaders bent on

violence, "never" seems wildly optimistic. In the meantime, the

location of that Australian memorial contains much wisdom. Our

leaders, and we who put them there, would do well to look daily into

the eyes of those commemorated in memorials across the world, and

recall the cost of our way of life.

Possibly disconnected ramblings of a mid-Generation-X-er trying to make sense of the phenomenon which is the emerging church.

2010/07/31

2010/07/07

gay bishop shock

This is getting to be rather a long-drawn-out saga.

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/newstopics/religion/7877839/Gay-cleric-blocked-from-becoming-Church-of-England-bishop.html

Blocking the man's appointment "because it would split the church" seems expedient in the short term, but the issue isn't going to go away, is it? And there seems little prospect of it not causing a split, when it finally does come to a head. So is there really any merit in deferring that day?

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/newstopics/religion/7877839/Gay-cleric-blocked-from-becoming-Church-of-England-bishop.html

Blocking the man's appointment "because it would split the church" seems expedient in the short term, but the issue isn't going to go away, is it? And there seems little prospect of it not causing a split, when it finally does come to a head. So is there really any merit in deferring that day?

2010/06/28

strange juxtaposition

I was walking past the University Museum this morning when I saw that they were setting up for (or maybe tearing down after) some kind of festival. The Museum is famous for having been in the 19th Century the location for an early debate on Darwin's Origin of Species, between T.E. Huxley and Bishop Samuel Wilberforce. As I recall, Huxley convincingly won the day. It is, rather self-consciously, a cathedral of science, and a humanist icon.

So I was a little perturbed to see as part of whatever was going on on the lawn outside seemed to include something looking suspisciously like an ark. My first reaction was to think "don't go there": surely this will get the nutters all excitable.

But on reflection, that seems far too defeatist. The story of Noah and the Ark plainly isn't about global geomorphology of 5000 years ago; it plainly isn't a treatise on practical biodiversity. We can benefit from it without taking those perspectives. Surely it's a story of wickedness and faithfulness; a story of redemption; a story of care for creation; a story of hope. It does belong to those of a rationalist disposition (as well as to those who believe that however many gigatonnes of water came into being briefly for a year, and then vanished again leaving little or no trace behind them).

I think that since I decided that the global cataclysm wasn't a matter of 'fact', I've been scared of to think of it at all: I'm a bit of a literalist at heart, still. But as a tale to teach us, it has a lot to say, and we mustn't shy away from that.

So I was a little perturbed to see as part of whatever was going on on the lawn outside seemed to include something looking suspisciously like an ark. My first reaction was to think "don't go there": surely this will get the nutters all excitable.

But on reflection, that seems far too defeatist. The story of Noah and the Ark plainly isn't about global geomorphology of 5000 years ago; it plainly isn't a treatise on practical biodiversity. We can benefit from it without taking those perspectives. Surely it's a story of wickedness and faithfulness; a story of redemption; a story of care for creation; a story of hope. It does belong to those of a rationalist disposition (as well as to those who believe that however many gigatonnes of water came into being briefly for a year, and then vanished again leaving little or no trace behind them).

I think that since I decided that the global cataclysm wasn't a matter of 'fact', I've been scared of to think of it at all: I'm a bit of a literalist at heart, still. But as a tale to teach us, it has a lot to say, and we mustn't shy away from that.

2010/06/17

quotes from Tomlinson

I'm reading Dave Tomlinson's Re-enchanting Christianity. I normally wait until I get to the end of a book before commeting, but this is so rich with pithy little thoughts that I have to report some of them. A proper review will follow.

One particularly striking section is about how we understand who Jesus is - this after a discussion of how to understand the bible and a contrast of 'literal realism', 'critical realism' and 'non-realism' in thinking about who God is. I was left gasping for air after I got to:

Well, if you put it that way, suddenly everything makes sense.

And then, there's the section on atonement. After discussing a number of ideas, we get something which perhaps we can put ona par with Chalke's 'cosmic child abuse; line which caught so much flack.

Ho ho. Nice pun, but makes the point well: he quotes from Wink who says that this theory portrays God as a cruel and unforgiving patriach 'unable to love as a decent parent should, trapped in his own rules that force him to commit a ghastly crime.'

All in all, this isn't a book for those of a sensitively evangelical disposition. But it's littered with food for thought. I love it!

One particularly striking section is about how we understand who Jesus is - this after a discussion of how to understand the bible and a contrast of 'literal realism', 'critical realism' and 'non-realism' in thinking about who God is. I was left gasping for air after I got to:

Only the doggedly rationalist mind imagines that truth is equated solely with fact.

Well, if you put it that way, suddenly everything makes sense.

And then, there's the section on atonement. After discussing a number of ideas, we get something which perhaps we can put ona par with Chalke's 'cosmic child abuse; line which caught so much flack.

Substitutionary atonement theory could be seen as a crime against divinity!

Ho ho. Nice pun, but makes the point well: he quotes from Wink who says that this theory portrays God as a cruel and unforgiving patriach 'unable to love as a decent parent should, trapped in his own rules that force him to commit a ghastly crime.'

All in all, this isn't a book for those of a sensitively evangelical disposition. But it's littered with food for thought. I love it!

2010/06/06

sometimes

Sometimes, I feel a great urge to tell people just to get over their hang-ups.

Divorced-bishops-to-be-permitted-for-first-time-by-Church-of-England.html

Divorced-bishops-to-be-permitted-for-first-time-by-Church-of-England.html

2010/05/30

alternative reality

I suppose that many of use inhabit alternative universes from time to time. A century ago, they existed mainly in literature, in theatre, and in children's games. Today, adults play role-playing games in alternative worlds, too, and computers exist to provide immersive experiences where you can be an Orc or an Elf; can defy gravity, or can explore the stars, or, Grand Theft Auto-style, can visit mayhem on a city without serious consequences.

But many people inhabit seemingly alternative realities without using such tools. The fanatical campaigner sees every event through the lens of their particular concern. You don't have to be clinically paranoid to worry about unwelcome stalkers or over-zealous government security agencies: many people's perception of the extent of monitoring is surely wide of the mark. One person's crazy obsession is another's real and present reality. The way the western education system has developed means that users of technology often have less than no understanding of how it works - that is, their ideas are actually wrong.

And as a member of the Christian community, this bothers me, because we seem to inhabit a reality far removed from that of our neighbours. It is not simply that we talk in jargon - every shared interest group does that. It is that when you strip this away, you still have a group of people whose view of the world is truly other, compared to that of those outside - those to whom we aspire to explain the reason for the hope we have ... This is a community which is profoundly odd compared to those with whom we rub shoulders with every day.

Was it always thus? Is this an inherent feature of being called out and different?

I'm not sure. It seems as if many of today's Christians are far more at odds with today's secular society than they have been for a mighty long time. Sure, when Europe was largely co-extensive with Christendom, there was a very widely shared view of a whole heap of topics - both among those we'd today identify as 'believers' and among those with a more tenuous or nominal connection with the Church. Today, Chrisitans generally embrace a kind of metaphysics which is pretty much incomprehensible to outsiders: to many, it must be considerably more weird than, say, The Force of Star Wars' Jedi Knights.

Does this matter? I'm inclined to say yes: we can construct all sorts of realities in our heads; we can reinforce them by rehearsing them together; we can embrace the most exotic metaphysics; we can build castles in the air. But that fervour doesn't make things true; it doesn't automatically make us closer to God; it sometimes seems to get in the way of our participating in his mission; it can distract us from truly following Christ; it really runs the risk of alienating the very people who need to see - and experience - the most excellent way.

But many people inhabit seemingly alternative realities without using such tools. The fanatical campaigner sees every event through the lens of their particular concern. You don't have to be clinically paranoid to worry about unwelcome stalkers or over-zealous government security agencies: many people's perception of the extent of monitoring is surely wide of the mark. One person's crazy obsession is another's real and present reality. The way the western education system has developed means that users of technology often have less than no understanding of how it works - that is, their ideas are actually wrong.

And as a member of the Christian community, this bothers me, because we seem to inhabit a reality far removed from that of our neighbours. It is not simply that we talk in jargon - every shared interest group does that. It is that when you strip this away, you still have a group of people whose view of the world is truly other, compared to that of those outside - those to whom we aspire to explain the reason for the hope we have ... This is a community which is profoundly odd compared to those with whom we rub shoulders with every day.

Was it always thus? Is this an inherent feature of being called out and different?

I'm not sure. It seems as if many of today's Christians are far more at odds with today's secular society than they have been for a mighty long time. Sure, when Europe was largely co-extensive with Christendom, there was a very widely shared view of a whole heap of topics - both among those we'd today identify as 'believers' and among those with a more tenuous or nominal connection with the Church. Today, Chrisitans generally embrace a kind of metaphysics which is pretty much incomprehensible to outsiders: to many, it must be considerably more weird than, say, The Force of Star Wars' Jedi Knights.

Does this matter? I'm inclined to say yes: we can construct all sorts of realities in our heads; we can reinforce them by rehearsing them together; we can embrace the most exotic metaphysics; we can build castles in the air. But that fervour doesn't make things true; it doesn't automatically make us closer to God; it sometimes seems to get in the way of our participating in his mission; it can distract us from truly following Christ; it really runs the risk of alienating the very people who need to see - and experience - the most excellent way.

2010/05/23

review: A New Kind of Christianity

A New Kind of Christianity: ten questions that are transforming the faith

A New Kind of Christianity: ten questions that are transforming the faithBrian McLaren

This is an important book. Since I attended the UK launch a mere three months ago, and have already (!) finished it, I guess you'd have to say it got my attention. McLaren has written enough that he must by now be regarded as "prolific". This book strikes me as one of his most important, though he seems to set more store by Everything must change. I think the new book is much better-edited than that one.

I do have the same criticism, though, as I wrote in my review of that book (and various commenters helped to explore): for all of wanting a new, more inclusive, less certain, more dynamic kind of faith, he does seem to dwell rather heavily on a dichotomous presentation: people used to think X, but a new way of looking at it is to think Y. For nearly all of his points, I'd much rather say that there tended to be an emphasis on X (but Y was present), but if we expand the emphasis on Y, we get a more rounded view, and that leads us to de-emphasise X.

Examples? Well, when you're talking about a question of emphasis, it's hard to pin them down. But let's try: he discusses various approaches to eschatology (that's the study of end times, not escapology :) ). And observes that these things shape our behaviour and priorities in the here and now. I don't doubt that - but the idea that we are all in thrall to whacky dispensationalism of one kind or another doesn't really seem to play out in the evangelical churches I'm familiar with. There is generally a very open-handed 'we can't really know for sure' kind of perspective preached: which also has an impact on how we live right now.

But for all his over-stated rhetoric, the perspective he brings is fresh, and his emphasis distinctive - even if I don't think it's all truly as novel as he (or his detractors) would suggest. And I know that he has many detractors. His writing has been criticised as theologically naive or historically amiss: there are certainly bits that I'd take with a pinch of salt, but this is a popular book, not a dry theological essay. I find proper theology very hard to cope with, but can read McLaren quite comfortably.

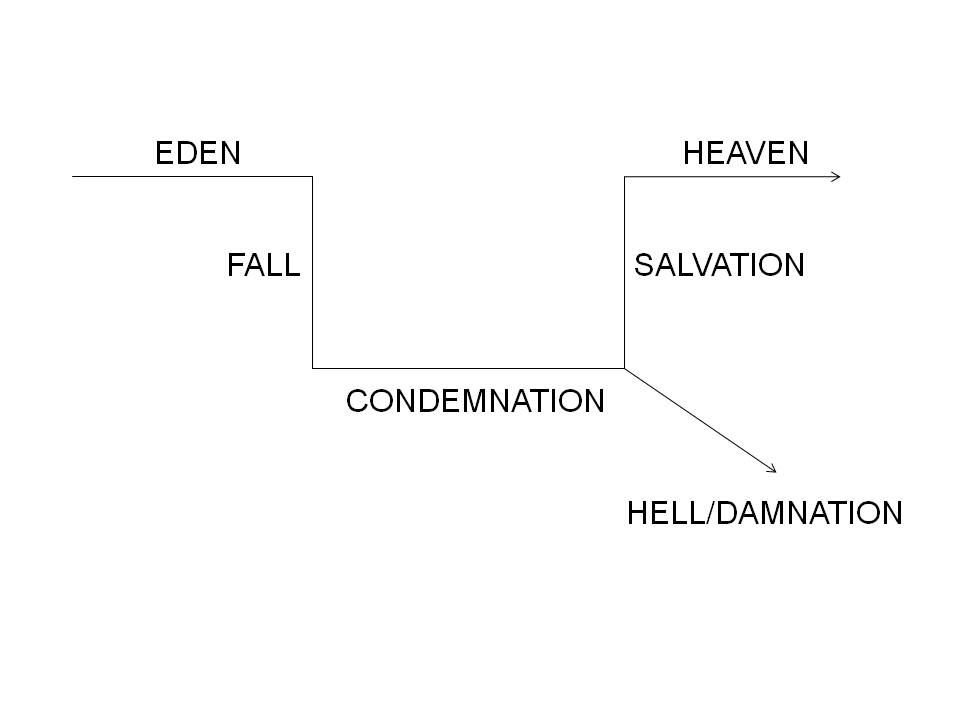

And for all my complaining, I certainly wouldn't claim we've "seen it all before". The first of his ten questions asks "What is the overarching storyline of the bible?" and the answer certainly isn't the one you learned in (evangelical) sunday school. He talks about this 'six-line diagram':

(h/t: thoughtsinpencil whose reproduction I have borrowed to save me drawing it for myself)

and he goes on to argue that, far from being the biblical story, this is the Greco-Roman Platonic story. I understand this is far from being a new observation. But he goes on to suggest other ways to frame the biblical story. This, in a sense, is fairly radical for an evangelical - as is the suggestion that the bible be read not as 'constitution' but as 'library'.

For his methodology remains evangelical, it seems to me: over and over, the chapters contain substantial exposition of particular passages of scripture. From his way of understanding the bible text, I guess we'd have to say that he does this because they are useful passages from which to draw lessons, rather than because they can be plucked from obscurity to prove a particular point. But his exegesis is generally convincing and helpful.

The methodology seems a little wanting in the chapter on "How should followers of Jesus relate to people of other religions?" I can't help thinking that drawing on the experiences of those contemporary with Jesus - in a very pluralistic society - would give us some insight. But his approach takes another line - based upon the Golden Rule.

I began by saying that this is an important book. I hope that many close to me will read it - I shall encourage them to do so, so that we can discuss it. A consistent theme across McLaren's writing is that we are in the midst of a shift in Christian thinking as profound as that which took place at the Reformation. I find it hard to imagine in 500 years that his name and work will carry the weight of Luther's or Calvin's today - but at least a part of me hopes that he will carry large numbers of people with him. I don't suppose he cares whether it's his name that gets attached to a new kind of Christianity, but he does look forward to something renewed. I'd have to agree with him that such thinking - and, as he stresses, acting too is needed and timely.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)